Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is a transformational approach that has the potential to deliver population-scale economic and social progress, and ensure environmental equity. Using digital transformation, open data, and open APIs, DPI promises resilient communities, responsive governments, and an improved quality of life for all.

The Digital India Stack has been the key enabler of India’s digital economy. It has patched leaks in delivering welfare benefits, brought hundreds of millions into the formal economy, empowered citizens, propelled small businesses, and promoted social, financial, and environmental equity.

There is no denying that DPI has been a spectacular success in India. Countries of the Global South are keen to replicate India’s success with poverty alleviation and its accelerated progress on human development indexes. The Indian government announced a Social Impact Fund with an initial seed capital of $25 million. The Social Impact Fund was envisioned as a government led initiative to fast-track DPI implementations in the Global South.

An ecosystem of companies have been created to facilitate policy, finance, educate and skill, architect solutions, and implement DPI services. DPI has been much heralded but it has not yet arrived in the Global South countries. Why isn’t DPI gaining momentum in other countries? How do we bridge this gap between the promise of DPI and the reality of DPI in the Global South? We look at four issues that are hindering adoption and ways to bridge the divide.

Leading with Identity

DPI outreach and initiatives are typically led with Digital Identity, with the messaging that Aadhaar was the foundation of India’s Digital Stack. Many governments view Digital Identity as a multi-year capital spend without clear visibility on the payout. Most countries have some form of ID (drivers license, passport, national ID, voter ID, etc) and don’t immediately see the need for yet another ID. They also point out India’s Supreme Court judgements that restrict use of Aadhaar.

We have shown that it was not Aadhaar but the Jan Dhan Yojana (Financial Inclusion Mission) that moved a quarter billion people out of poverty, and how OTP-based authentication (instead of Aadhaar authentication) can work for services. Most of the Global South countries are data poor, and a data-first strategy is the key to DPI success. To understand how countries can fast track DPI by following India’s successes while avoiding the missteps, read The DPI Playbook — Data First, not Digital First

DPI Playbook – Data First, not Digital First

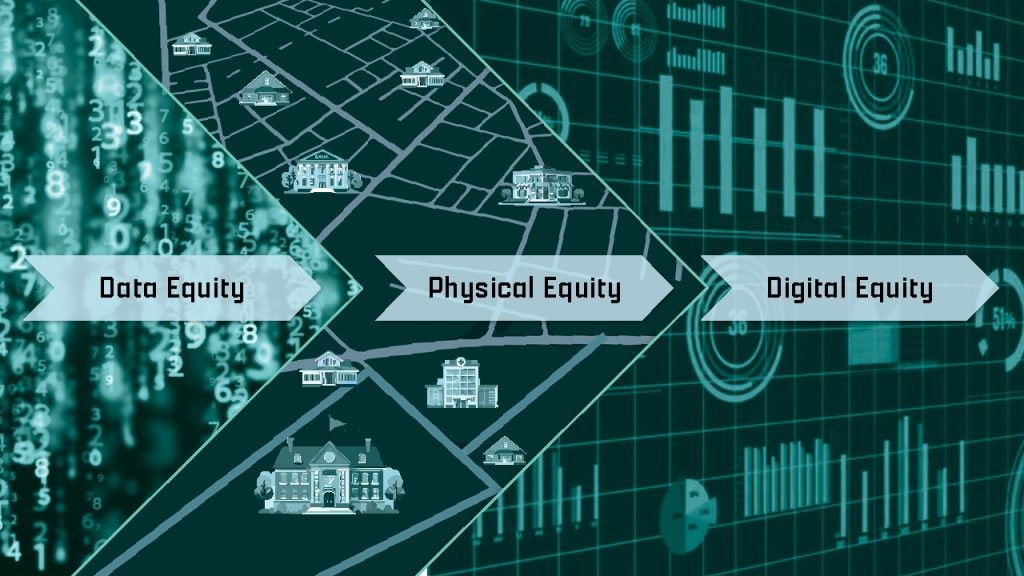

If there is one takeaway from India’s DPI success, it is that data equity must precede physical equity, and physical equity must precede digital equity. Instead of leading with digital-first policies, the secret to success is to lead with data-first policies.

Putting focus on Open Source

Open source is software where the source code is made available and can be used as-is, modified, enhanced, and freely distributed. While the software is technically free, the total cost of ownership is hard to measure and quantify. As the source code is public, it also opens itself to malicious actors who can exploit vulnerabilities in the code. For open source software to be successful, it requires a critical mass of developers who are actively contributing to it, that can detect and fix vulnerabilities and identify any backdoors.

Open source also ties you to a specific computer language and implementation. If Aadhaar was coded in Java, and you open source it, then the only option is to implement Digital Identity in Java. It also may have dependencies on older versions of libraries that may in-turn have known vulnerabilities. It restricts an entity from taking advantage of more modern computer languages, or adapting it to locally available skill sets, or taking advantage of security through obfuscation, which a proprietary implementation provides.

Instead of open source, the focus should be on open APIs and open data. This provides flexibility and will not constrain other countries to a specific implementation or language. Open data/open APIs are also key for creating data exchanges.

Open source creates dependency. Open data and open APIs creates ownership and will empower and democratize ownership. To understand how open data, open APIs, and open maps are key to effectively managing shared physical and digital commons, read Bangalore Floods – A Call for Open Data.

Bangalore Floods – A Call for Open Data

Instead of focusing on open source, make the focus open data, open maps, and open APIs.

Defining DPI

A significant challenge is the lack of consensus on the definition of DPI. Numerous siloed government digital transformation initiatives are labeled as DPI. The African payment platform M-Pesa is frequently categorized as DPI, despite high transaction fees and Vodafone and Huawei being the primary beneficiaries.

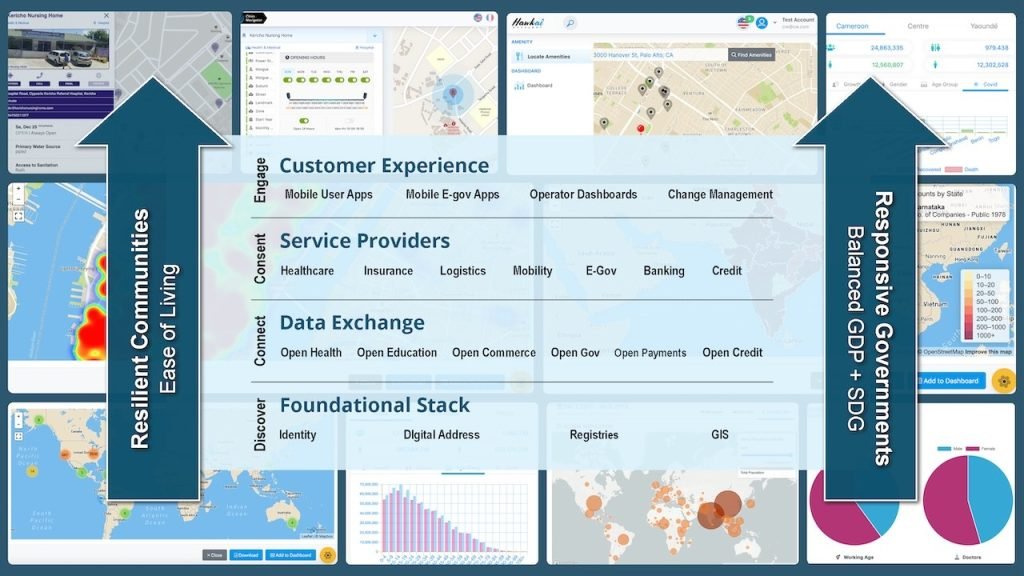

DPI is not a service. It is an open architecture that enables the building of population-scale services. Open data and open APIs ensure that data is not fragmented, but federated; that data movement is not impeded but can be exchanged seamlessly across entities. This architecture ensures local control and security of data, while enabling national access, portability, and insights. To understand the DPI architecture, read On Data – Poverty, Quality, and Fragmentation.

On Data – Poverty, Quality, Fragmentation

Digital sovereignty, enabled by DPI, ensures autonomy and self-determination by providing countries control over their data, infrastructure, software, and digital assets. Digital sovereignty will allow countries to control their digital destiny.

Measuring Impact of DPI

The success of a digital transformation can be measured by access and usage. A resident will adopt a digital service if it is accessible, intuitive, and inclusive. While access and usage metrics measure the performance of the service, they do not provide a measure of the impact on the quality of life of the community.

There is already global consensus on SDG metrics that provides a measure for a community’s socio-ecological progress. DPI impact on the community will be measurable as progress in SDGs on hunger, health, education, gender equity, access to water/sanitation/power, clean air and water. To understand SDG metrics and how DPI can accelerate the achievement of SDGs, read Achieving SDGs – An Actionable Framework.

Achieving SDGs – An Actionable Framework

The Metraa (Measure/Track/Reform/Accelerate/Achieve) framework leverages open data, digital transformation, Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), and sustainable models of service delivery. The Metraa framework’s actionable metrics will provide transparency into progress towards goals and an accelerated path towards achieving them.

Bridging the Divide

Hawkai Data has years of experience working on-the-ground in Global South countries, data-skilled thousands, created locale-specific data models, proposed projects around DPI, and delivered apps and dashboards for measuring status and progress on SDGs. We have been analyzing and reporting on services built on the Digital India Stack since 2021.

Our video and articles on DPI are at https://hawkai.net/digital-public-infrastructure/

Our video and articles on accelerating SDG and measuring impact of DPI are at https://hawkai.net/sustainable-development/

Our video and articles on the Digital India Stack services, and why customer experience is key to adoption, are at https://hawkai.net/customer-experience/

If you have any questions, talk to us at info@hawkai.net, or follow us on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/company/hawkai-data/, or connect with us at https://hawkai.net.