India spends about 3% of its GDP, or around $120 billion, on healthcare. There are approximately 400 million households in India, which averages to a household spend of ₹2000 per month on healthcare.

About 70% of India’s population is covered by government insurance, social health schemes, and private insurance. That leaves 30% of the population vulnerable to financial hardships and medical debt in the event of any adverse health events. This population segment is neither poor enough to qualify for government health subsidies nor rich enough to afford private health insurance. For this segment, however, a monthly premium of ₹2000 per household is affordable.

Can we create a healthcare model that can deliver universal healthcare with zero out-of-pocket expenses using a ₹2000 monthly subscription model for comprehensive healthcare? Can India provide universal and affordable health insurance at 3% of its GDP?

We show that it can, by reforming the insurance model to a subscription model paid directly to a primary care provider, with with the provider assuming the risk/insurance coverage for secondary and tertiary care. Before we discuss this new healthcare model, we must first understand the state of Indian health insurance.

Delay, Deny, Deduct

My father-in-law recently underwent a cataract surgery for both eyes over the span of a few weeks. The hospital billed him ₹42,000 for each eye and ₹2250 for tests to confirm that he needed the cataract surgery. The hospital did not have a cashless arrangement with the insurance, and it was a pay-first, claim-later process.

First were the delays. The text in the claim forms was minuscule, in five-point font, and had to be filled out using a magnifying glass. Subsequently, another hospital visit was required post-surgery to obtain the necessary signature for the claim form.

Then came the denial. The insurance informed us that another hospital in the city had lower rates and the surgery should have been performed there. The claim would be rejected if we could not satisfactorily explain why the surgery was not performed at the other hospital. More communication followed stating that the other hospital was much further away and not easily accessible.

Finally, they made the payout but with deductions. For one eye, the insurance paid ₹40K and in a few weeks, they paid ₹34K for the other. We pointed out that the two claims were for the same surgery, done at the same hospital, and the hospital had billed exactly the same amount. On what basis did the insurance deduct different amounts? The insurance replied with the specific reasons for the deductions.

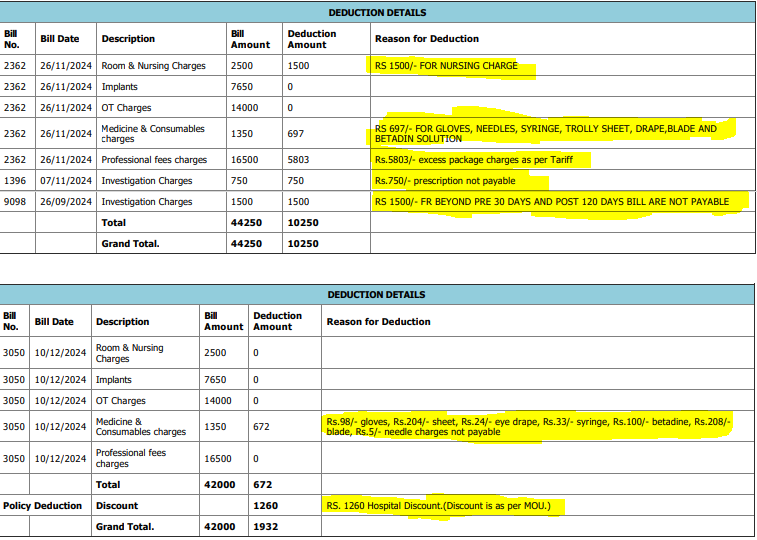

Deduction details highlighted

At this point, we wrote back saying that it looks like there was a policy change in between the two claims, asking to be sent the dated policy document where this new agreement is mentioned?

This prompted the insurance company to return ₹5803, the deduction for ‘excess package charges as per Tariff’. We are still contesting the remaining charges and maintain that only the two preoperative investigation charges, for ₹750 and ₹1500, are legitimate deductions. The deductions raise questions about the competence of insurance companies to evaluate medical necessity. Specifically, do they possess the clinical expertise to decide if essential items like nursing care, gloves, needles, syringes, trolley sheet, blades, and Betadine solution are unnecessary for a cataract surgery?

Our experience is not unique. Unfortunately, it is the norm. For an insurance buyer, is there some metric to rank insurance companies and make an informed choice?

Opacity, Friction, and the Uninformed Consumer

Indian insurance companies highlight their claim settlement ratio (CSR), which is the ratio of the claims resolved to the claims received. A 90% CSR means that 10 out of 100 claims were rejected (they were deemed fraud, or outside of policy, etc). CSR is mostly an indicator of potential fraud. This KPI is useful to an insurance company to blacklist providers. To a buyer of insurance, the CSR number is pretty much useless.

Health insurance companies rely on a business model built on opacity and friction. Their policy documents are intentionally opaque, the claim process overtly complex, and companies understand that upon successfully navigating this friction, even a partial payout is seen as a win and unlikely to be disputed. The claims department is seen as a profit center and incentivized to put its own interest over the interest of its policyholders.

Health insurance in India does not cover primary care. Policies only cover secondary and tertiary care, with many requiring an overnight stay at a hospital. Rarely is the distinction between inpatient (requiring 24 hrs or more) coverage and outpatient (no overnight stay) coverage spelled out in the policy documents.

Cataract surgery is an outpatient procedure and does not require hospitalization. Policies that cover cataract surgeries typically have waiting periods, and do not cover preoperative tests, postoperative medicines, and follow-up visits. The details are in the fine print. The lack of transparency and non-existent customer support is intentional and disadvantages the policyholder.

Friction also exists between the insurance and the healthcare provider. This friction arises from a lack of mutual trust. The insurer wants to control costs and manage risks. They want to prevent fraud, overtesting, and unnecessary treatments. The healthcare providers want fair reimbursement and quick payments. The lack of trust results in prior authorization requirements that lead to delays in treatment and upfront out-of-pocket payments. Prior authorization intends to control costs, but it has become a pervasive barrier to care with insurance determining medical necessity.

A better KPI is the claims paid out ratio (CPR), which focuses on the value of the settled claims. For settled claims, if the total valid claims value was ₹10 crores and the insurance pays out ₹8 crores, then the CPR is 80%. CPR is a good indicator of the friction between the insurance company and its provider network. Insurance companies should aspire for a 100% CPR (instead of highlighting their CSR).

A 100% CPR can be attained with 100% cashless agreements between the insurance and provider network, and will ensure a frictionless experience for the patient, with no surprise medical bills and inflated out-of-pocket expenses. While a 100% CPR benefits the policyholder, achieving it requires mutual trust between the insurance and the healthcare providers.

The insurance must trust that the procedures were required and necessary. The hospital must trust that reimbursements will be made on time. Achieving 100% CPR requires the hospital and insurance to coordinate seamlessly, putting the patient’s interests first. Hospitals see little value in enabling cashless claims as the pay-first claim-later model allows them to control the price for a medical procedure, frees them from integrating with multiple insurance providers, and revenue is accounted for as soon as service is delivered. This trust deficit is a result of a misaligned marketplace, which increases administrative overheads for the insurance, inflates costs for the provider, and leads to higher premiums for the policy buyer.

Misaligned Marketplace

A free market forces companies to innovate, improve efficiencies, and deliver products and services that a customer needs. Markets are aligned when innovation leads to improved margins and profits for the company and better outcomes for the customer. The friction between the healthcare provider and the insurance provider results in a misaligned marketplace, where innovations and improved efficiencies at the healthcare provider, results in lowered revenues for the provider and doesn’t translate to lowered premiums for the consumer.

Curing a patient is not a sustainable business, while chronic treatment is recurring revenue. The marketplace’s misaligned incentives create a situation where the desired outcome of a healthy community is not in the interest of the healthcare provider, as it leads to reduced revenues. The healthcare market is aligned towards sickness care not wellness care, towards procedures not prevention.

Every market entity has become corporatized and is focused on profits. Hospital profits demand maximizing revenue on each patient. Insurance profits demand minimizing payouts for each patient. In this tug-of-war for profits between the provider and the payer, it is the patient who suffers and forced to cover the spread.

Health insurance companies are financial entities and lack the clinical expertise to judge medical necessity. We are letting insurers dictate patient care, on what is necessary and covered and what is not. Medical necessity and hospital charges must be determined based on patient needs and not on a company’s financial incentives. For the insurer and the healthcare provider, profits determine the care that a patient receives.

What the policyholder is asking for is transparency, no surprise medical costs, and for insurance to stop dictating patient care and provide comprehensive coverage without fine print. A misaligned marketplace encourages hospitals to overtest, overprescribe, and perform unnecessary procedures. This forces the insurance companies to assume a claim is fraudulent, and the onus is on the patient to prove otherwise.

Recipe for Disaster

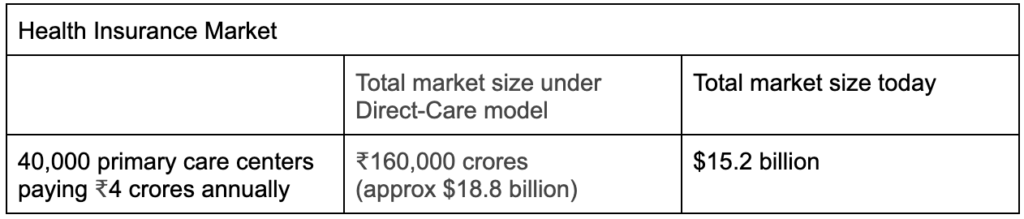

Indian insurance companies model themselves around US health insurance companies. US health insurance companies are all about corporate profits and are hugely profitable companies. In 2024, US health insurance companies made $31 billion in profits (in comparison, the total market size of the Indian insurance companies in 2024 was $15.2 billion). It is no wonder that Indian insurance companies try to copy US health insurance products.

The US spends over 18% of its GDP on healthcare (around $4.9 trillion in 2023), but healthcare remains deeply fragmented, with less than optimal patient outcomes, higher mortality rates, poor patient experience, high pharmaceutical costs, and huge amounts of waste. Blindly copying US health insurance products is a recipe for disaster.

While Indian insurance companies have tried to model their policies around US insurance offerings with an eye towards higher profits, they have not invested the same energy in what US health insurance does right. US healthcare is cashless – you get the care, the provider bills the insurance, and the insurance pays based on the policy. India, for the most part is still pay-first, claim-later. You have to make sure that you have the money upfront, pay the hospital, and then fight it out with the insurance to get the money back. If the hospitalization did not drain you, the insurance will.

While the pay-first, claim-later model works for the hospitals, it is a double whammy for the patient. The patient has to first raise the money for the procedure from friends and family, and then battle it out with the insurance to claim it back. Many insured often resort to crowdfunding platforms like GoFundMe and Ketto to cover hospital expenses.

Misaligned incentives between the provider and the payer have created a healthcare system designed for debt. In the US, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 has led to higher deductibles, and increased out-of-pocket costs, with about 100 million people living with medical debt. Meanwhile, US health insurers have raked in about $400 billion in profits since the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

In India, the pay-first, claim-later model is systematically pushing patients deeper and deeper into debt. A government report estimates that a quarter of the population incur catastrophic health expenditures, and 7% of India’s population is pushed into poverty every year because of healthcare costs.

As the US healthcare model has shown, spending more on a broken model is not the solution. The healthcare model has to be reformed, where market efficiencies ensure that innovation is rewarded, waste is eliminated, and profits of the providers and payers are aligned with patient outcomes and community health.

Direct-Care Subscription-Based Healthcare

The Direct-Care Subscription-Based healthcare model right-aligns market forces, eliminates waste, rewards innovation, and ensures that the profits of the providers and payers are aligned with community health.

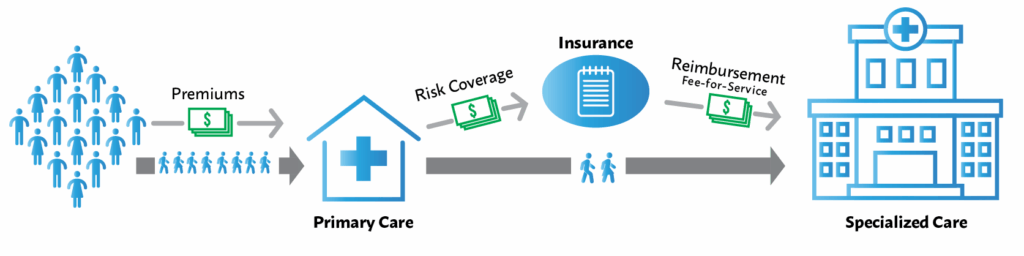

Direct-Care Subscription-Based healthcare model

Subscription-based healthcare offers healthcare as a service and is provided by the primary care provider. The primary care provider is responsible and accountable for community health. In this model, a fixed rate is paid per month per family to a primary healthcare provider of their choice. This provides them with all their healthcare needs with no further out-of-pocket expenses, other than potentially a copay, a low flat fee for doctor visits, prescription drugs, or tests. This model provides predictable revenue for the primary care provider, reduces administrative overheads, and eliminates claim processing for the healthcare subscriber.

The only touchpoint that a healthcare subscriber has is their primary care provider. The primary care provider buys group risk insurance that covers secondary and tertiary care. It is the primary care provider that authorizes secondary/tertiary care. Fraud is disincentivized as that would increase group insurance premiums.

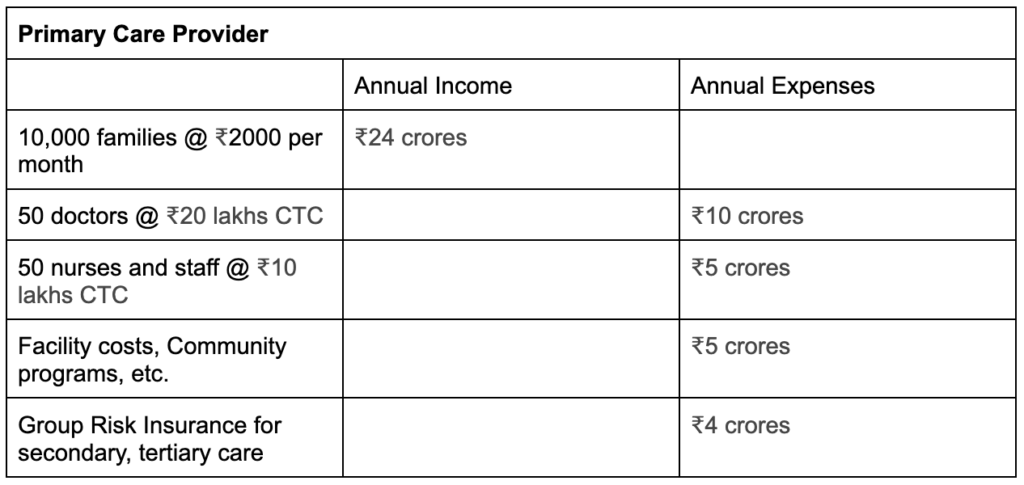

India spends around 3% of its GDP on healthcare. This averages to ₹2000 per household per month. Let’s assume an average of ₹2000 per family per month paid directly to the primary care provider. A provider that signs up 10,000 households will have an annual revenue of ₹24 crores.

Income/Expense for Primary Care Provider

Assuming 400 million households, and 10,000 households per primary care center, would require 40,000 primary care centers across India.

Health Insurance market size under the Direct-Care Subscription-Based model

In this model, health insurance companies also come out ahead, with the market size for health insurance increasing to about $18.8 billion. Health insurance companies in India have low claim ratios. Low claim ratios are indicative of high distribution costs and operational costs. The retail nature of insurance makes customer acquisition costs expensive. The Direct-Care model will significantly lower customer acquisition costs and distribution costs, as insurance products need to be targeted to only the 40,000 primary care providers. Targeting primary care providers increases the size of the risk pool, enables better risk modeling, and ensures that actual claim payouts do not significantly deviate from the actuarially determined model.

The subscription-based direct-care model right-aligns market forces, increases the number of primary-care doctors, increases the health insurance market size, eliminates waste, and minimizes claim processing. It will improve health outcomes and provide universal and affordable healthcare at 3% of India’s GDP.

Cashless, Frictionless, and Seamless

Epic Systems is the market leader in Electronic Health Records (EHR). It is privately owned and generates around $5 billion in revenues. Epic Systems maintains longitudinal health records for over 325 million individuals worldwide and dominates the EHR market with over 40% market share. The US EHR market is highly fragmented, with hundreds of vendors offering EHR products, with a few like Epic Systems and Oracle Health (previously Cerner) controlling large segments of the market.

One of the reasons for the high costs of healthcare is fragmented data and incompatible IT systems across providers and payers. The lack of an integrated digital infrastructure where patient records can be accessed seamlessly across providers and payers inflates costs and leads to medical misdiagnosis, repeat testing, inappropriate medications, and polypharmacy.

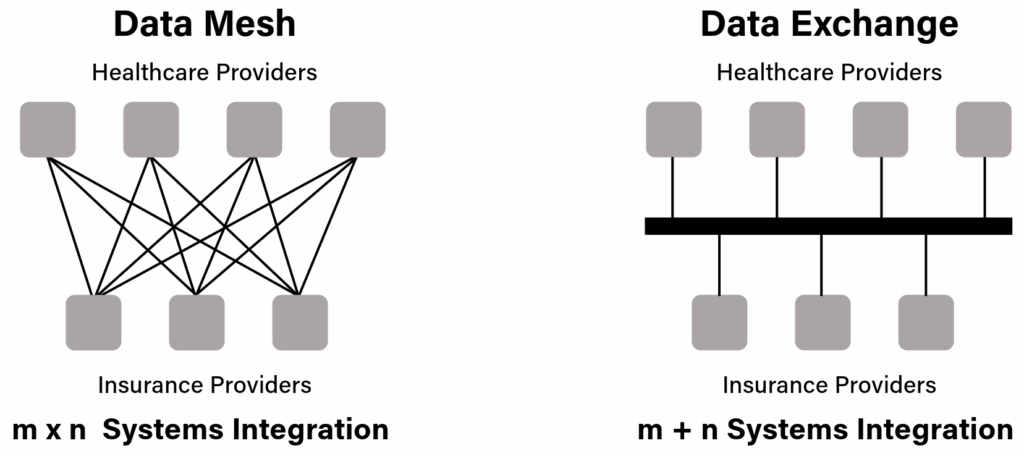

Fragmented data and the lack of a common data exchange protocol force insurers to have to integrate with each provider’s EHR systems. This creates inefficiencies, hinders collaboration, limits insights, and increases costs. Every major technology provider and EHR vendor is promising to transform healthcare with AI. In a fragmented market, a proprietary transformation only leads to more fragmentation, more siloed data, vendor lock-ins, and significantly inflates integration costs.

A Health Data Exchange facilitates secure data sharing between providers and payers and enables frictionless claims processing and portable health records

An open API data exchange will ensure that health records are portable and available to any healthcare provider as needed. Standardized data exchange protocols will eliminate data fragmentation and simplify integrations with multiple payers. To address this, India is creating the backbone digital infrastructure and data exchanges for an integrated healthcare system as a Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI).

The Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) is creating the healthcare digital stack that includes a healthcare facilities registry, a healthcare professionals registry, and a national data exchange that allows providers and payers to seamlessly integrate and process claims, and enables portable health records that will significantly improve care delivery.

Registries, open federated data, and open APIs will allow for nation-level datasets to be de-identified and made available for shared research. The availability of these population-scale datasets will give data analytics, ML, and AI workloads the data volumes to avoid algorithmic bias, researchers the ability to replicate and verify results independently, companies the ability to accelerate the development of new drugs and treatments, and countries the ability to craft data-driven public health policies and localized healthcare interventions.

Digital Public Infrastructure will ensure that the entire healthcare system is cashless, frictionless, and seamless. National data exchanges will ensure that claims and health records are portable, secure and seamless across providers, payers, and patients. It will significantly lower the cost of healthcare, delink healthcare from employment, and make businesses more competitive, governments more responsive, and communities more resilient.

Free Healthcare Coverage for All

India spends around 3% of its GDP on healthcare. With the Direct-Care subscription model of healthcare, the National Digital Health Stack, and with direct-benefits transfer to the primary care providers, India can deliver free healthcare to all at 3% of GDP.

The Direct-Care Subscription model will eliminate the need for consumers to buy opaque health insurance products. It will disentangle health insurance from employment, significantly reduce the cost of hiring for businesses, provide predictable revenue to primary healthcare centers, and make health professionals accountable for community health outcomes.

The Direct-Care Subscription model will incentivize early interventions, prioritize prevention over treatment, palliation over procedures, and quality of life over quantity of life. It will create healthy communities, profitable healthcare businesses, and enhance a nation’s social capital.

Further Reading and References

The US spent $4.9 trillion, about 18% of GDP, on healthcare in 2023. Reforming the healthcare system to a subscription-based direct-care model, with the primary care provider assuming the risk/insurance for secondary/tertiary care, will deliver universal and affordable healthcare at 6% of GDP, enabling over $3 trillion in savings. Read more at, The Rash that Cost $1538

Read more about the Direct-Care Subscription-Based model and how it compares to other healthcare delivery models, Transforming Healthcare – Better Outcomes at Lower Costs

Read more about the state of India’s healthcare system, The Missing Middle – Towards Universal and Affordable Health Coverage

Read more about Digital Public Infrastructure – https://hawkai.net/digital-public-infrastructure/